To enjoy a symphonic performance, an average audience member doesn’t need to know the difference between a pizza and a pizzicato — the term for plucking violin strings rather than bowing them — or that in musical notation “piano” refers not to the 88-key instrument but to playing softly.

But an understanding of just how much practice, effort and talent goes into uniting the 72-odd members of an orchestra in glorious sound can help increase appreciation and understanding of why symphony orchestras exist.

An arcane code

When attending a symphony concert, you might have noticed beads of sweat collecting on the back of the conductor’s neck or spied a violinist leaning over to the musician next to them to quietly exchange a word or two.

But what you’ve probably never seen is the conductor abruptly stopping the music as it builds with tremendous tension to pronounce, “Every sound you make continues into the universe.”

During a recent rehearsal for the San Antonio Philharmonic’s performance of Richard Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde, conductor Sebastian Lang-Lessing did just that. Lang-Lessing asked musicians to imagine their crescendos — a musical direction to start quietly and gradually build volume — flying out into space and becoming a sound that “goes into the black hole of the universe.” The musicians scribbled notes on their scores in response.

Mary Ellen Goree, principal second violin of the San Antonio Philharmonic, receives notes from Concertmaster Sarah Silver Manzke during a rehearsal in October at First Baptist Church of San Antonio. Credit: Bria Woods / San Antonio Report

These are not standard musical notations, but a common way conductors seek to bring centuries-old music to life.

“A musician is only given this very arcane code, and it’s a visual code, which is not even the right medium,” said Christopher Wilkins, music director of the Akron Symphony and guest conductor of the Philharmonic during its Nov. 18-19 performances.

“In order to translate from black marks on a page into this wondrous world of sound, so many choices have to be made. And there’s no way that a composer can write those all down on the page,” Wilkins said.

In technical terms, Lang-Lessing was asking string players not to stop their bows at the end of the note, ending the vibration, but to lift the bow to let the sound reverberate.

The longtime conductor then raised his wire-thin white baton and led the strings through the crescendo in question. After three tries, with further instruction and imploring, the string section achieved his desired result. Violins and violas began together at a whisper, then launched into an overwhelming chord that filled the 1,200-seat performance hall.

From silence to magic

Ironically, the conductor’s job begins in silence.

Wilkins said he’ll begin his work long before the concert, sitting at his desk poring over the score and imagining the sounds it describes.

Before a conductor ever approaches the podium to direct musicians, the score should be “as familiar to you as the map of your own hometown,” he said.

Akiko Fujimoto, who leads the Mid-Texas Symphony, said that work begins weeks in advance. “Ninety-five percent of the work of a conductor is done before the concert,” she said.

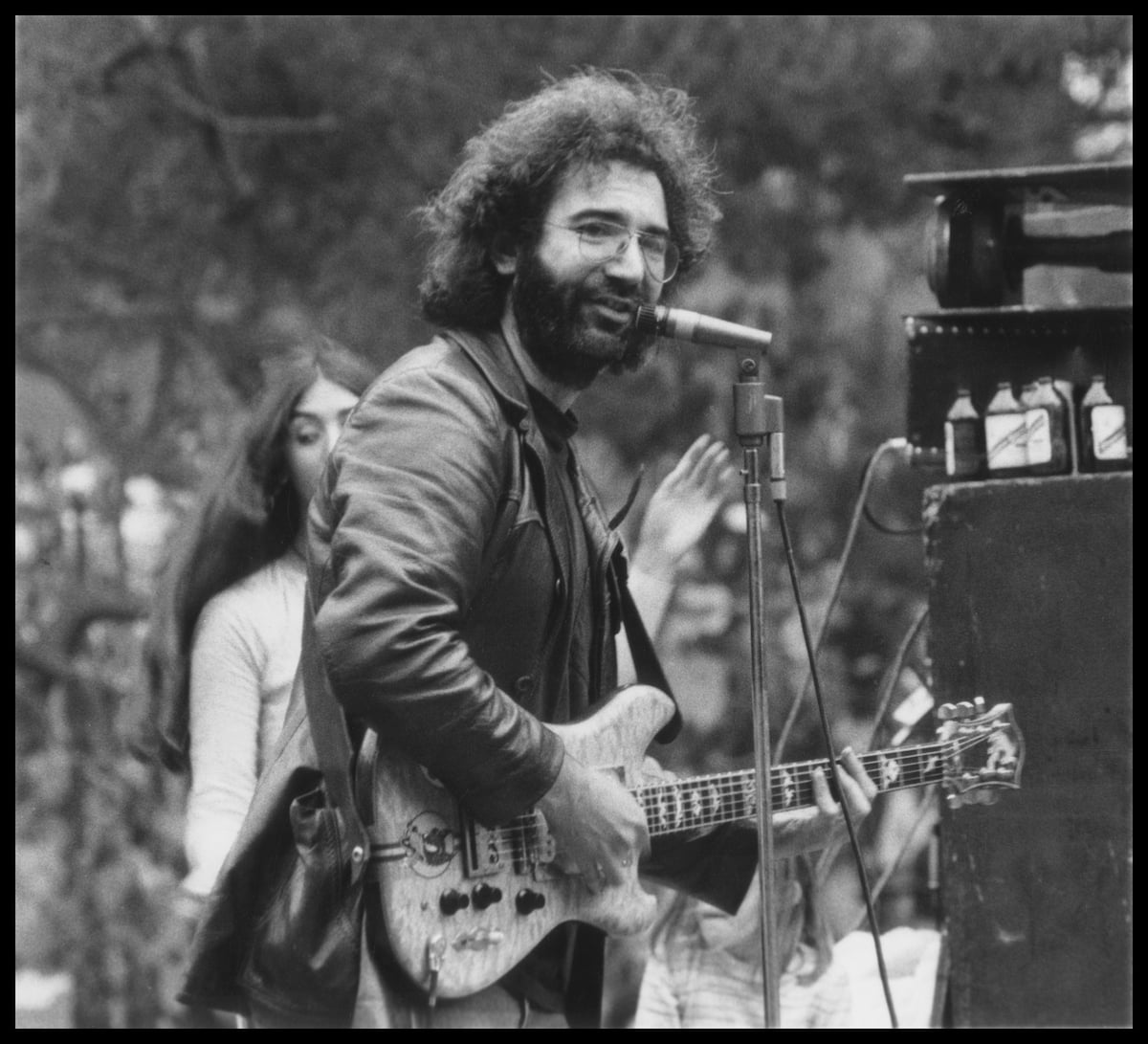

San Antonio Philharmonic bassist Tom Huckaby makes notes in his sheet music during a rehearsal at First Baptist Church of San Antonio in October. Credit: Bria Woods / San Antonio Report

San Antonio Philharmonic bassist Tom Huckaby makes notes in his sheet music during a rehearsal at First Baptist Church of San Antonio in October. Credit: Bria Woods / San Antonio ReportLike Wilkins, she’ll study the composition, learning each instrument’s parts. When she finally greets the orchestra the week of the concert for its first rehearsal, she said she’d better know her stuff. “The first rehearsal is sort of like the final exam, where we display everything we’ve studied and decided.”

Professional musicians have already spent hours practicing their individual parts, preparing to play flawlessly when they join their fellow musicians onstage.

They might be as familiar as the conductor with a particular composer’s work, but their stylistic approaches might differ. The job of the conductor is to join all those individual musical voices in one unified effort.

“It’s just a miracle how an orchestra can even do what it does,” Wilkins said. “I give a downbeat, and suddenly, out of a professional orchestra comes this magical sound that’s balanced and in tune and wondrously variegated. And it can go from just a whisper to shattering levels [of sound].”

Wilkins likens the experience to a hundred-ton aircraft taking off. “If I’m conscious and thinking about it, I think, how does this even work? I mean, what does this thing weigh? How can you possibly use air, which would seem to weigh nothing, to lift itself?”

Listening to a recorded symphony on headphones can convey the beauty of the music, he said, “but you don’t have an appreciation of people actually somehow cooperating at the most minute levels, enormous subtleties of not only producing sound but listening to each other. It’s just an astonishing human achievement.”

Ignacio Gallego, cellist with the San Antonio Philharmonic, reads his sheet music during a rehearsal at First Baptist Church of San Antonio in October. Credit: Bria Woods / San Antonio Report

Ignacio Gallego, cellist with the San Antonio Philharmonic, reads his sheet music during a rehearsal at First Baptist Church of San Antonio in October. Credit: Bria Woods / San Antonio ReportNever be discouraged

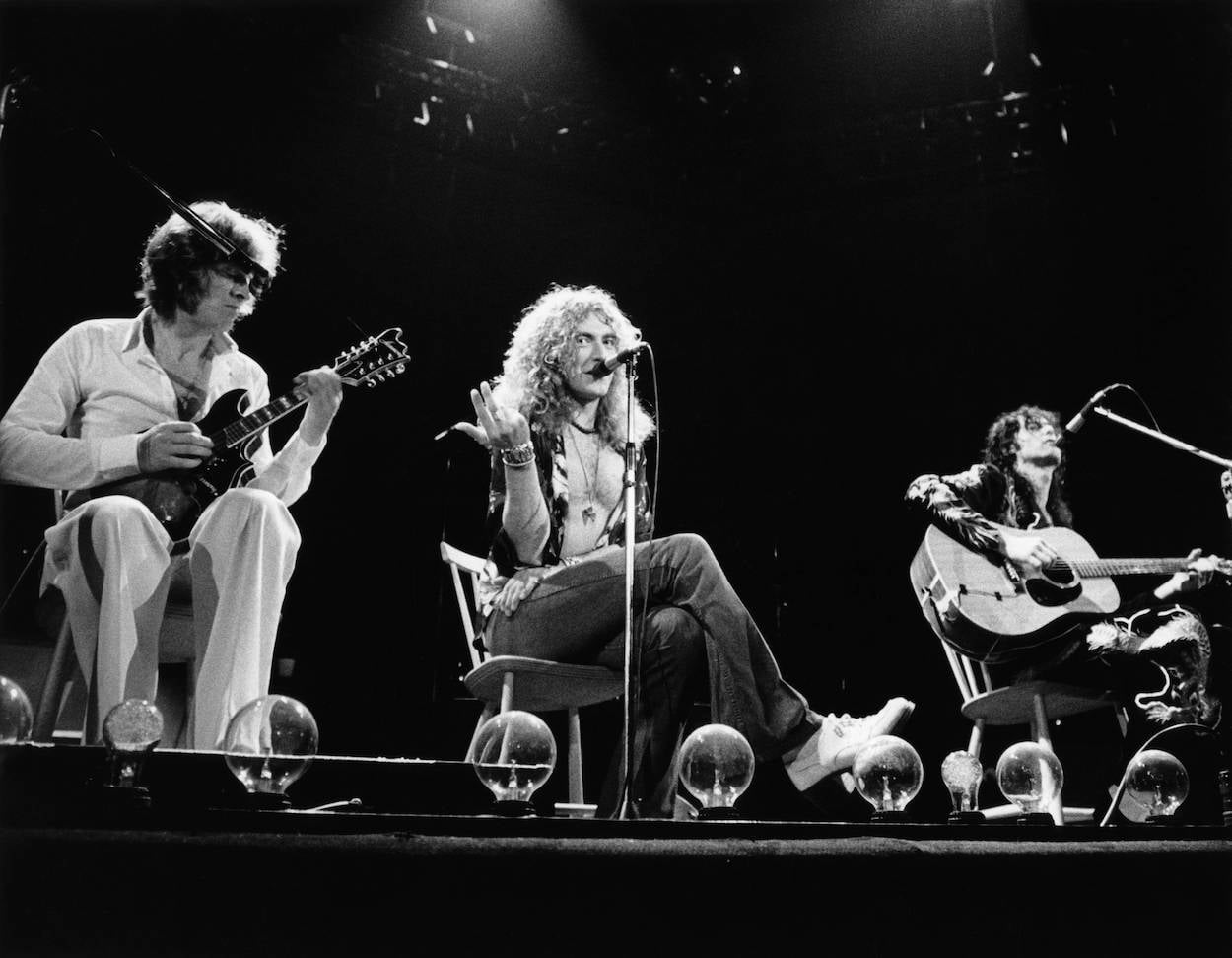

If the experience of a symphony can seem distant or overwhelming, focus on the conductor the next time you venture out to a concert, Wilkins said. Like Lang-Lessing working with separate sections during the rehearsal, the person on the podium will communicate with the musicians onstage in an almost telepathic way, drawing that dramatic crescendo out of them with a facial expression or, with a subtle gesture, reminding the trombones to back off a bit to let the violas be heard.

The conductor’s pivots from one section to another, from the woodwinds (so named for the tiny wooden reeds musicians blow through to make sound) to the brass, for example, can illuminate an almost conversational back-and-forth between melodies each section carries.

Conductor Sebastian Lang-Lessing motions directions to the musicians of the San Antonio Philharmonic. Credit: Bria Woods / San Antonio Report

Conductor Sebastian Lang-Lessing motions directions to the musicians of the San Antonio Philharmonic. Credit: Bria Woods / San Antonio Report

While one expert concertgoer might note the subtleties of the bassoonist’s legato phrasing — meaning a smooth transition between notes — a new orchestra fan might simply come away emotionally uplifted by a thundering piano solo or moved by that rushing crescendo Lang-Lessing and the strings worked so hard behind the scenes to achieve.

Fujimoto offered advice to anyone intimidated by their unfamiliarity with the whole “arcane code” of symphonic music: use the internet.

“The problem with [live] music is it’s in real time and evaporates, so you can’t rewind,” she said. Many orchestras share program notes online, often not only explaining the music but lending context of the composer’s life and times that inform their music. A little knowledge goes a long way, Fujimoto said, and adds up toward a deeper appreciation of the form.

And, even if it’s still all a bit too much, “never be discouraged,” she advised. “If nothing else, just soak up the sound and enjoy watching the musicians play live in front of you.”

If you can feel the vibration and the joy of live music, Fujimoto said, “you’ve already won.”

English (US)

English (US)